A possibly better Data Encryption Standard

A proposal for an Enhanced Data Encryption Standard

Let me preface this whole post by saying this idea was developed purely for exploration purposes, as this was a proposed project for a class of Applied Cryptography that I’m attending in a Cybersecurity Master’s, so it’s mostly academic, without the rigor part. It does, however, show that some tweaks here and there can make a difference, in this case, in terms of performance and security which is pretty much what we want in encryption algorithms.

I’ll start by giving a simple primer on the Data Encryption Standard, if you already know how it works you can jump to the right place by clicking here

All code shown can be found in a couple of repositories that implement this improved DES. These implementations differ only in the programming languages used, C and Rust:

The Data Encryption Standard

Before we dive into a possibly better Data Encryption Standard, referred to as DES from now on, it’s important to understand the basics of it.

DES is a symmetric-key encryption algorithm, developed in the early 1970s. It uses 56-bit keys and, most importantly, something called Substitution Boxes, which I’ll refer to as S-Boxes from now on. It’s a block cipher algorithm, meaning your message will be split into multiple blocks (8 bytes, in DES) and then encrypted using one of multiple block cipher modes, such as Electronic Code Book, Cipher Block Chaining, etc. which you can read about here.

In symmetric-key encryption algorithms, you’ll essentially have one key, which is shared by both parties present in the encryption/decryption of a message.

I urge you to read some documentation on DES, such as the wonderful wiki page on it, seriously, wikipedia has really good cryptography content.

DES is no longer used in practice (I hope) because it’s just not secure anymore. The insecurity of DES stems from the fact it uses really short keys, at 56 bits only, as well as being vulnerable to certain attacks exploring its S-Boxes, because they’re known to everyone.

Feistel Networks

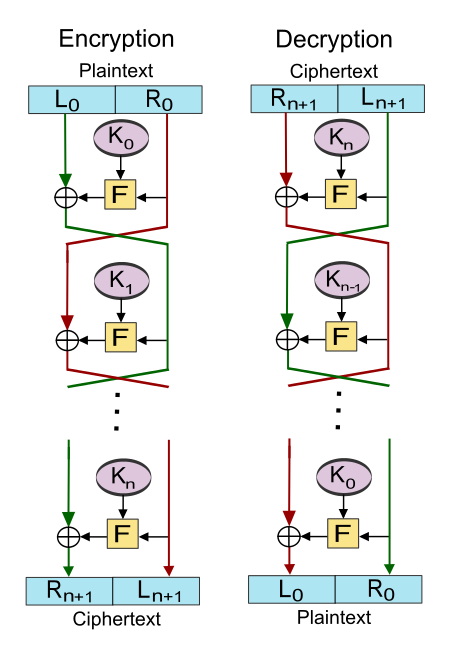

DES is an implementation of something called a Feistel Cipher. Often, you’ll see this construction named Feistel Network, because it repeats a process multiple times, or rounds.

At its core, a Feistel Network will have a function that’s run multiple times (rounds), that takes two inputs:

- A block of bytes, such as 8 bytes for DES;

- A round key, also known as a subkey. These are keys generated from the main key, you know, the one the encryptor and decryptor have.

This function will work by splitting the block in 2, usually called the Left and Right parts, and then xoring one side with the output of the round function. At each round, the sides swap and this is repeated a fixed amount of rounds (16 for DES).

Here’s a view of this in action:

wikipedia: Feistel

wikipedia: Feistel

S-Boxes

At their core, S-Boxes, or Substitution Boxes are simply arrays of values that are used to obscure the connection between the result, call it ciphertext, and the Key. Normally, they will take a certain number of bits and convert them into bits. can be different than . The reason these can be expressed as arrays of values, even though they’re matrices, with dimension , is that they can be represented with vectors of length .

You can look at an example from the wiki here.

On DES, we have 8 S-Boxes, with predefined values, which you can look at online.

P-Boxes

Permutation Boxes, or P-Boxes, conceptually, aren’t a lot different from the S-Boxes. The whole idea here is that you’ll have multiple input bits, for which you get an output position, thus shuffling the input set around. These are used in conjunction with S-Boxes, where together, they make it incredibly difficult to get a connection between a ciphertext and a key (this is called Shannon’s Principle of Confusion)

DES!

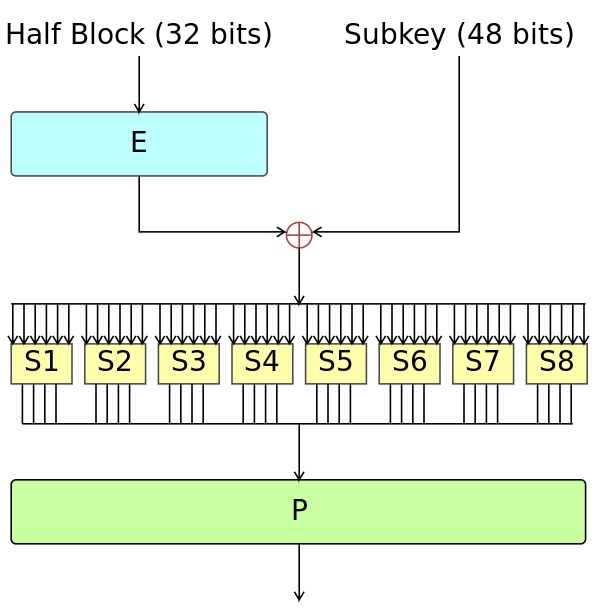

Well, now that you have a sense (hopefully) of S-Boxes, Feistel Networks and the fact they need Round Functions, here’s the one that DES uses:

wikipedia image for the DES Feistel Function

wikipedia image for the DES Feistel Function

So, let’s dissect the image! You see that the first thing it does is to get half the block and run it through an E process. This stands for Expansion and it’s a process in which half of those bits (16) will be duplicated, resulting in 48 bits total. This result is then xored with the round key (subkey) and we’re left with a 48-bit value.

Now, this value is split into 8 parts of 6 bits, and each part is sent to an S-Box. As you’ve seen earlier, these will produce m bits from bits, in this case, they produce 4 bits of output from 6 of input.

Finally, these 32 resultant bits are reordered based on a permutation rule. This rule is set in a P-Box.

This is it! run this thing for 16 rounds, for each block and you get DES encryption.

A better DES

Now we get to the fun part, let’s explore a way of making DES more secure by doing two things:

- Increase key size to 256 bits

- Use 16 S-Boxes of 256 bytes each, instead of 8. Make these S-Boxes Key-Dependent, Deterministic, and not dependent on each other

By the way, some welcome side-effects of this is that we won’t need P-Boxes anymore, as well as no more key expansions, even simplifying our implementation

Let’s continue, point 1) is really easy, just make the key larger. Point 2) however, is a bit more tricky so let’s tackle it.

We need a way to make the S-Boxes based on our key, and they have to be deterministic, so both parties can generate the same ones. We also need to find a way to make these Key-Dependent S-Boxes not depend on each other, which is not hard to do if we just use different keys and these can be obtained from a main key quite easily.

Hopefully, since we’re getting rid of quite a bit of processing from DES, by removing the permutation and expansion parts, we should effectively get a more performant algorithm, as well as more secure since 256-bit keys are pretty hard to crack and the S-Boxes won’t be known beforehand.

So, let’s craft our solution…

Key-Dependent S-Boxes

This is where your creativity could come into play. Think about it for a second, for us, an S-Box is an array of bytes, something like:

uint8_t sbox = {

0x01, 0x02, 0x03, 0x04, 0x05, 0x06, 0x07, 0x08, 0x09, 0x0a, 0x0b, 0x0c, 0x0d, 0x0e, 0x0f, 0x10,

0x11, 0x12, 0x13, 0x14, 0x15, 0x16, 0x17, 0x18, 0x19, 0x1a, 0x1b, 0x1c, 0x1d, 0x1e, 0x1f, 0x20,

0x21, 0x22, 0x23, 0x24, 0x25, 0x26, 0x27, 0x28, 0x29, 0x2a, 0x2b, 0x2c, 0x2d, 0x2e, 0x2f, 0x30,

0x31, 0x32, 0x33, 0x34, 0x35, 0x36, 0x37, 0x38, 0x39, 0x3a, 0x3b, 0x3c, 0x3d, 0x3e, 0x3f, 0x40,

0x41, 0x42, 0x43, 0x44, 0x45, 0x46, 0x47, 0x48, 0x49, 0x4a, 0x4b, 0x4c, 0x4d, 0x4e, 0x4f, 0x50,

0x51, 0x52, 0x53, 0x54, 0x55, 0x56, 0x57, 0x58, 0x59, 0x5a, 0x5b, 0x5c, 0x5d, 0x5e, 0x5f, 0x60,

0x61, 0x62, 0x63, 0x64, 0x65, 0x66, 0x67, 0x68, 0x69, 0x6a, 0x6b, 0x6c, 0x6d, 0x6e, 0x6f, 0x70,

0x71, 0x72, 0x73, 0x74, 0x75, 0x76, 0x77, 0x78, 0x79, 0x7a, 0x7b, 0x7c, 0x7d, 0x7e, 0x7f, 0x80,

0x81, 0x82, 0x83, 0x84, 0x85, 0x86, 0x87, 0x88, 0x89, 0x8a, 0x8b, 0x8c, 0x8d, 0x8e, 0x8f, 0x90,

0x91, 0x92, 0x93, 0x94, 0x95, 0x96, 0x97, 0x98, 0x99, 0x9a, 0x9b, 0x9c, 0x9d, 0x9e, 0x9f, 0xa0,

0xa1, 0xa2, 0xa3, 0xa4, 0xa5, 0xa6, 0xa7, 0xa8, 0xa9, 0xaa, 0xab, 0xac, 0xad, 0xae, 0xaf, 0xb0,

0xb1, 0xb2, 0xb3, 0xb4, 0xb5, 0xb6, 0xb7, 0xb8, 0xb9, 0xba, 0xbb, 0xbc, 0xbd, 0xbe, 0xbf, 0xc0,

0xc1, 0xc2, 0xc3, 0xc4, 0xc5, 0xc6, 0xc7, 0xc8, 0xc9, 0xca, 0xcb, 0xcc, 0xcd, 0xce, 0xcf, 0xd0,

0xd1, 0xd2, 0xd3, 0xd4, 0xd5, 0xd6, 0xd7, 0xd8, 0xd9, 0xda, 0xdb, 0xdc, 0xdd, 0xde, 0xdf, 0xe0,

0xe1, 0xe2, 0xe3, 0xe4, 0xe5, 0xe6, 0xe7, 0xe8, 0xe9, 0xea, 0xeb, 0xec, 0xed, 0xee, 0xef, 0xf0,

0xf1, 0xf2, 0xf3, 0xf4, 0xf5, 0xf6, 0xf7, 0xf8, 0xf9, 0xfa, 0xfb, 0xfc, 0xfd, 0xfe, 0xff, 0x00

};So, we have 256 bytes, each byte ranges from 0x00 to 0xff and the only way to change the S-Box, knowing we cannot have repetitions inside it, is to shuffle it somehow. Some people will probably find a Pseudo Random Number Generator, because these are deterministic, and find a way to connect a key to it, allowing them to have that value as the seed for a shuffling algorithm. You repeat this 16 times, for each S-Box, with different subkeys and voila! you got your boxes.

In this post, I’ll be doing this a little differently, on my research, I came across a great article by Kazys Kazlauskas, Gytis Vaicekauskas and Robertas Smaliukas named “An Algorithm for Key-Dependent S-Box Generation in Block Cipher System”, which you can find here.

The proposed algorithm to shuffle these S-Boxes, based on a key is as follows:

The key: You take a secret key and put it in a vector of unsigned bytes, from the interval . Take the 256-bit key “SuperSecretKeySuperSecretKey1234” as an example. I’ll explain later how we make sure every key is 256 bits, but for now assume a user provided this key on some sort of prompt, to encrypt a message. Now, the C code for this could look something like:

uint8_t *key = "SuperSecretKeySuperSecretKey1234";

for (int i = 0; i < 32; i++) {

// key(i) will allow you to iterate over every byte

}Obviously, you could create an array of bytes from that string, but you don’t have to.

Next, we need our initial S-Box, which will be an array of bytes, starting from 0, all the way to 255. This makes it a vector with all values in the interval . For performance reasons, it may be good practice to keep this vector hardcoded, just to avoid those extra cycles of building it (every cycle counts in encryption!), but let’s just make it with a loop, for now:

uint8_t sbox[256];

for (int i = 0; i < 256; i++) {

sbox[i] = i;

}Now that we have our key and sbox ready, we can move forward with the algorithm.

You’ll see some mod mentions, e.g. means, get me the remainder of divided by . If you’re used to C-like programming languages, this is achieved using the modulus operator, as such:

int remainder = 20 % 2; // remainder of 20/2.We start by computing an initial value , which will depend on all the bytes from our key. It goes as follows:

Ok, so, the above mathy symbols mean:

- For each byte in our key, calculate the remainder with 256 and add this value to , our initial value.

- For each byte in our sbox, run the shuffle function, which I’ll show now.

With our initial value , our loop index and the key length , we can do the following, with from 0 to 255:

So, we’re calculating the remainder of the sum of the values of our S-Box at the indexes and with . Then, with this, we’re setting to the sum of with the value of our key at index , mod 256.

Now, comes the actual shuffle/swap part. We have two indexes and , so we’ll swap the values of our S-Box at these positions.

We’re done! We have successfully shuffled an S-Box. I know the explanation above is quite dense for people who aren’t used to reading mathy things and code speaks for itself, so let me present all of it in code:

void shuffle_sbox(uint8_t sbox[], uint8_t *key) {

uint8_t j = 0;

uint8_t key_sum = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < 32; i++) {

key_sum += key[i] % 256;

}

j = key_sum;

uint8_t k = 0;

uint8_t tmp = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 256; i++) {

k = (sbox[i] + sbox[j]) % 32;

j = (j + key[k]) % 256;

tmp = sbox[i];

sbox[i] = sbox[j];

sbox[j] = tmp;

}

}It’s pretty simple, right?

Round Keys

Ok, so, an astute reader would have realized by now that the S-Box shuffling above has a problem based on the rules described in A Better DES, which is the fact we need a different key for each S-Box, otherwise all S-Boxes will be dependent on each other.

One super easy way to solve this, and by no means the safest, is to keep an index of our S-Boxes, using it to modify the key in each shuffling round (for each S-Box).

So, it goes like this:

Or, in code:

if (sbox_index > 0) {

for(int i = 0; i < 32 - 1; i++) {

key[i] = key[i + 1] ^ sbox_index;

}

}We’re also checking the sbox_index is greater than 0, because we don’t modify the key for the first round.

Please note, this is not the best way to do this, it has some security vulnerabilities in and of itself, a better way would be to use something similar to the AES Key Scheduler!

Guaranteeing 256 bit keys

Well, this one is not complicated at all, all I’m doing is using SHA256 hashing on top of whatever key is provided, this way, we always get a 256-bit string no matter what. We use the hashed version as our key, easy peasy.

In C, the way I do this is by using the openssl/sha.h library, as such:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <openssl/sha.h>

uint8_t *get_sha_256(char *input) {

uint8_t *key = calloc(32, sizeof(uint8_t));

key = SHA256(input, strlen(input), NULL);

return key;

}The Feistel Function

We need a function that creates some entropy, given 4 bytes (half of our block size), using only the S-Box, in order to remove the need for P-Boxes and initial/final bit permutations.

This is not my implementation, it’s from the class’s project guidelines, as I’ve mentioned in the beginning, this was all done for academic (and fun) purposes, following the guidelines from an Applied Cryptography class.

Our Feistel Function is as follows:

With this, we get our output half block. It’ll become more evident in the next part.

Wrapping up the implementation

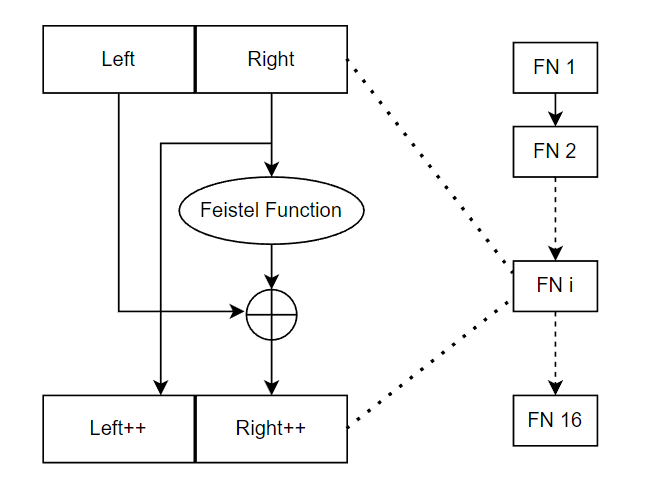

Now that we have the means to generate Key-Dependent S-Boxes and got our keys sorted. Let’s put it all together.

reproduced from an applied cryptography class’s coursework, by Professor André Zúquete

reproduced from an applied cryptography class’s coursework, by Professor André Zúquete

This is pretty much the same as DES, but the Feistel Function is a lot simpler, let me show you the code:

#define SBOX_SIZE 256

#define BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES 8

#define NUM_SBOXES 16

#define KEY_SIZE 256

#define KEY_SIZE_BYTES (KEY_SIZE / 8)

#define BLOCK_HALF_SIZE (BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES / 2)

typedef struct {

uint8_t *original;

uint8_t *encrypted;

uint64_t encrypted_len;

} EDES_Result;

uint8_t sboxes[NUM_SBOXES][SBOX_SIZE];

bool initialized = false;

EDES_Result *encrypt(uint8_t *input, uint64_t file_len, uint8_t *key) {

// Check if context has already been initialized, if not, generate the sboxes

if (!initialized) sbox_init(key);

EDES_Result *result = (EDES_Result*) malloc(sizeof(EDES_Result));

result->original = input;

uint8_t *padded_result = pad(input, file_len, BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES, &result->encrypted_len);

uint8_t *cipher_result = calloc(result->encrypted_len, sizeof(uint8_t));

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < result->encrypted_len / BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES; i++) {

process_block(padded_result + (i * BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES), cipher_result + (i * BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES), sboxes);

}

// We don't need the padded message anymore, not freeing this will leak memory

free(padded_result);

result->encrypted = cipher_result;

return result;

}

void process_block(uint8_t block[BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES], uint8_t result_block[BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES], uint8_t sboxes[NUM_SBOXES][SBOX_SIZE]) {

uint8_t left[BLOCK_HALF_SIZE] = {block[0], block[1], block[2], block[3]};

uint8_t right[BLOCK_HALF_SIZE] = {block[4], block[5], block[6], block[7]};

uint8_t output[BLOCK_HALF_SIZE];

uint8_t left_tmp[BLOCK_HALF_SIZE];

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_SBOXES; i++) {

for (int i = 0; i < BLOCK_HALF_SIZE; i++) {

left_tmp[i] = left[i];

left[i] = right[i];

output[i] = 0;

}

int index = right[0];

output[3] = sboxes[i][index];

index = (index + right[1]) % SBOX_SIZE;

output[2] = sboxes[i][index];

index = (index + right[2]) % SBOX_SIZE;

output[1] = sboxes[i][index];

index = (index + right[3]) % SBOX_SIZE;

output[0] = sboxes[i][index];

for (int i = 0; i < BLOCK_HALF_SIZE; i++) {

right[i] = left_tmp[i] ^ output[i];

}

for (int i = 0; i < BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES; i++) {

result_block[i] = i < BLOCK_HALF_SIZE ? left[i] : right[i - BLOCK_HALF_SIZE];

}

}

}

void sbox_init(uint8_t *key) {

initialized = true;

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_SBOXES; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < SBOX_SIZE; j++) {

sboxes[i][j] = j;

}

gen_sbox(sboxes[i], key, i);

}

}

void gen_sbox(uint8_t sbox[], uint8_t *key, uint8_t sbox_idx) {

if (sbox_idx > 0) {

for(int i = 0; i < KEY_SIZE_BYTES - 1; i++) {

key[i] = key[i + 1] ^ sbox_idx;

}

}

uint8_t j = 0; // initial value

uint8_t key_sum = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < KEY_SIZE_BYTES; i++) {

key_sum += key[i] % SBOX_SIZE;

}

j = key_sum;

uint8_t k = 0;

uint8_t tmp = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < SBOX_SIZE; i++) {

k = (sbox[i] + sbox[j]) % KEY_SIZE_BYTES;

j = (j + key[k]) % SBOX_SIZE;

// Swap sbox[i] with sbox[j]

tmp = sbox[i];

sbox[i] = sbox[j];

sbox[j] = tmp;

}

}That’s a whole lot of code! Welcome to the C Programming language :) By the way, you’ll see that we’re using padding as well, which is needed. The code for that, as well as an explanation of how it works, can be found in a post I’ve done about PKCS#7, here

To decrypt, it’s very similar, we just process the block in inverse form. Also, this code below could be simplified, that is, you don’t need two functions to process blocks since the only thing that differs is that the left will be swapped with the right.

Additionally, note that here, instead of going through the S-Boxes from first to last, we’ll go from last to first.

EDES_Decryption *edes_decrypt(uint8_t *input, uint64_t len, uint8_t *key) {

// Check if context has already been initialized, if not, generate the sboxes

if (!initialized) sbox_init(key);

uint64_t num_blocks = len / BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES;

uint8_t *message = calloc(len, sizeof(uint8_t));

for (int i = 0; i < num_blocks; i++) {

process_block_inverse(input + (i * BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES), message + (i * BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES), sboxes);

}

EDES_Decryption *result = (EDES_Decryption*) malloc(sizeof(EDES_Decryption));

result->cipher_text = input;

uint8_t *unpadded_result = unpad(message, len, BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES, &result->message_len);

result->message = unpadded_result;

// We don't need the message anymore, not freeing this will leak memory

free(message);

return result;

}

void process_block_inverse(uint8_t block[BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES], uint8_t result_block[BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES], uint8_t sboxes[NUM_SBOXES][SBOX_SIZE]) {

uint8_t left[BLOCK_HALF_SIZE] = {block[0], block[1], block[2], block[3]};

uint8_t right[BLOCK_HALF_SIZE] = {block[4], block[5], block[6], block[7]};

uint8_t output[BLOCK_HALF_SIZE];

uint8_t right_tmp[BLOCK_HALF_SIZE];

for (int i = NUM_SBOXES - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

for (int i = 0; i < BLOCK_HALF_SIZE; i++) {

right_tmp[i] = right[i];

right[i] = left[i];

output[i] = 0;

}

int index = left[0];

output[3] = sboxes[i][index];

index = (index + left[1]) % SBOX_SIZE;

output[2] = sboxes[i][index];

index = (index + left[2]) % SBOX_SIZE;

output[1] = sboxes[i][index];

index = (index + left[3]) % SBOX_SIZE;

output[0] = sboxes[i][index];

for (int i = 0; i < BLOCK_HALF_SIZE; i++) {

left[i] = right_tmp[i] ^ output[i];

}

for (int i = 0; i < BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES; i++) {

result_block[i] = i < BLOCK_HALF_SIZE ? left[i] : right[i - BLOCK_HALF_SIZE];

}

}

}This is it! Please remember all this code’s in a repository at E-DES.

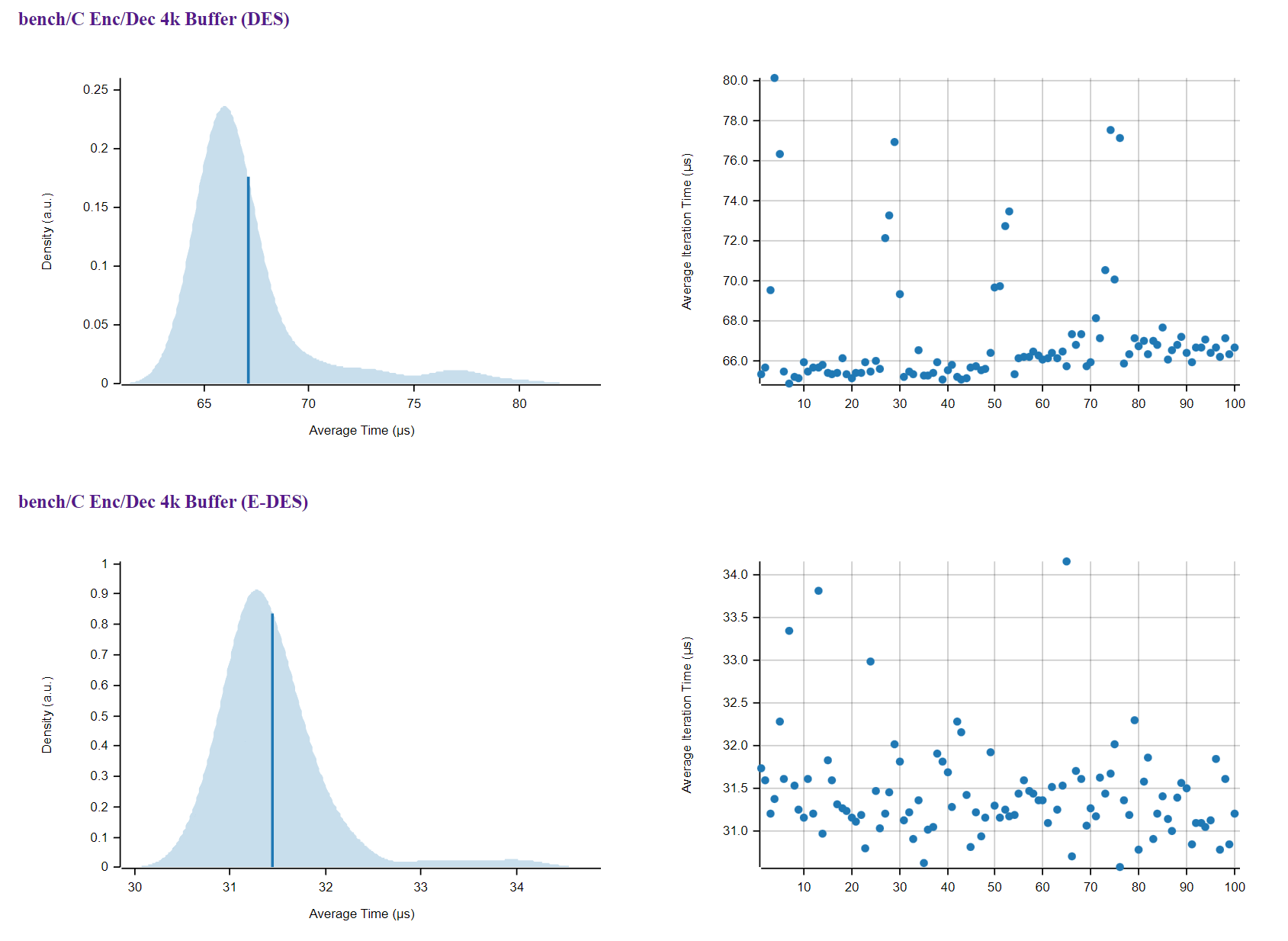

Benchmarks

To benchmark, I’ve run an encryption + decryption round, on a 4096B random buffer (from /dev/urandom), 100k times and measured the Wall-Time of execution.

This process was running with DES, using openssl, as well as the improved version, comparing the two.

I will spare you the code for the benchmark, it’s here if you want to look at it.

Turns out that, on average, this new implementation is about 2.2x times faster!. For fun, I’ve created a wrapper of my C implementation to use in Rust, and ran it with Criterion, a benchmarking framework, here’s the graphical overview of DES vs. E-DES. By the way, E-DES just stands for Enhanced DES.

Criterion’s benchmark DES vs. E-DES C implementation

Criterion’s benchmark DES vs. E-DES C implementation

I’d say it’s blazing fast, but that’s Rust’s thing, in which case you can check the results in its repo

Final Notes

This is not anything you, or anyone else should use in any real scenario, at least unless someone stress tests it to oblivion and makes sure it’s good. It was a really fun little project that had me learning a bunch of things I didn’t know existed.

I decided to create this post to journal the process of creating this, I know it’s convoluted and I may have said some weird things in here since I’m by no means a crypto expert, but I hope it’s as interesting to you as it is to me.

Thanks for reading!